Progress!!! obscured by black smoke (Guest post by Jim Ayers.)

And how these 'art-deco' locomotives looked so cool. They became the public face of technical progress - locomotives that looked like expensive automobiles that looked like "ZOOM".

Sep 16

And how these 'art-deco' locomotives looked so cool. They became the public face of technical progress - locomotives that looked like expensive automobiles that looked like "ZOOM".

This entry would ideally consist of one word. No. Lisa Hajjar begins her essay “Does Torture Work? A Sociolegal Assessment of the Practice in Historical and Global Perspective” by stating, “If an article addressing the question ‘does torture work?’ had been solicited for the Annual Review of Law and Social Science a decade ago, it would have seemed as anomalous as an article entitled ‘does genocide work?’” (2009). A longer entry is necessary, and requires the author to ask about the definition of ‘work’ regarding the function of torture. Given that torture does not ‘work’ to procure intelligence, why have people working under the direction of the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States tortured people? To put the question crudely, what ‘work’ does torture do? What ‘work’ has been wrought by torture in the last two decades?

In “Crucifixion as Parodic Exaltation,” Joel Marcus presents a question in interpreting the use, during the Greco-Roman era, of prolonged, spectacularly public executions on elevated, crosswise structures: Why? There were speedier ways to kill someone. What work was the cross doing for the authorities of that era? He explains, “in the ancient Greco-Roman context, the idea of bringing a person down by raising him up must still have struck people as incongruous, and presumably those responsible for the practice would have been cognizant of this irony” (Marcus 2006). The “human object lesson” that was crucifixion “gained maximum visibility and hence optimal deterrent power.” Marcus writes “this strangely ‘exalting’ mode of execution was designed to mimic, parody, and puncture the pretentions of insubordinate transgressors by displaying a deliberately horrible mirror of their self-elevation.” He continues, “people of any class who had not shown proper deference to the emperor,” people who “demonstrated disdain for imperial rule,” were particularly subject to this form of torture. “The graphic tableau of the cross” is, Marcus argues, “a prime illustration of Michel Foucault’s thesis that the process of execution is a ‘penal liturgy’ designed to reveal the essence of the crime” (2006, 79).

In Fear: The History of a Political Idea, intellectual historian Corey Robin enumerates different uses of fear as a means of control. Specifically, Robin is interested in “political fear,” by which he means “a people’s felt apprehension of some harm to their collective well-being . . .” (2004, 3). He links different ways that political fear works, and his analysis is helpful for thinking about how torture works politically. Robin explains that “political fear,” while “often associated with government acts,” is not unrelated to “the fear a woman has of her abusive husband, or the worker of her unkind employer.” Although by some accounts “these fears” are merely “personal, the product of an unfortunate but entirely private derangement of power,” Robin continues, “they are political . . . [and] spring from pervasive social inequities.” These established rules of order are, in turn, sustained by fear. Fear “sustain[s] long traditions of rule over women and workers” (2004, 3).

Robin explains that, during times of war, the form of fear used most obviously is to present “public objects of apprehension and concern” (2004, 18). The effort to normalize torture in the United States, and, to some extent, in other countries participating in the ongoing “war against terror” has involved depicting Muslim people as “public objects of apprehension and concern.” There has been another, related, political use of fear—a fear that “hover[s] quietly about the relationships between the powerful and the powerless, subtly influencing everyday conduct without requiring much in the way of active intimidation” (19). Linking Marcus’s insight about the use of crucifixion as a “display” or “liturgy” to warn against insubordination to state power, torture may “work” to, as Hajjar words it, “deter opposition and signal the costs of resistance.” Hajjar quotes Henry Shue’s 2004 essay on torture, noting that the purpose of torture may be “intimidation of persons other than the victim.” She continues, summarizing other essays on “modern torture regimes”: “Terroristic torture is an invisible spectacle because people are made fearful of torture that they know is occurring but do not actually see” (Hajjar 2009, 323). Torture, as a spectacle, as a possibility, as a hidden but known reality, may be used as part of a complex of social control.

Logistics of torture

The applicable definition of “encyclopedia” in the Oxford English Dictionary is as follows: “A literary work containing extensive information on all branches of knowledge, usually arranged in alphabetical order.” This encyclopedia entry—this set of words containing information about torture – comes from a location central to one agency’s pursuit of intelligence. This entry on torture comes from the vantage point of North Carolina in 2019. The North Carolina Commission on the Inquiry of Torture issued a report in September, 2018: “Torture Flights: North Carolina’s Role in the CIA Rendition and Torture Program.” The commission included legal scholars, clergy, veterans, and physicians working together to document how and why Johnston County Airport in Smithfield, North Carolina was used as a launching site as part of the United States Rendition, Detention, and Interrogation program. North Carolina was involved in trafficking people by air to places where people were assigned the task of torturing other people in the presence of other people tasked with recording words.

In his “Foreword” to the report, Alberto Mora, Former General Counsel (2001-2006), Department of the U.S. Navy identifies the basics. He explains that the “connection between North Carolina and the government-sponsored torture of the era is clear: aircraft operated by at least one local company, based at North Carolina airfields that were subsidized by North Carolina revenues and subject to a measure of North Carolina regulation, and flown by North Carolina pilots, were engaged in the transport of dozens of captive individuals to multiple foreign sites, some managed by U.S. officials, others by foreign governments, to be tortured” (Read 2018, 4). This 2018 report was part of an ongoing effort by citizen groups across the United States to document U.S. sponsored torture. There was a saying about the Italian government under Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini. Tourists were said to have noted that Mussolini “made the trains run on time.” In their report, the North Carolina Commission documents how North Carolina made the rendition planes run on time. This report was barely discussed outside of activist circles.

Linguistics of torture

In the United States, the word “torture” has become diluted in the cultural lexicon. This entry is written from a state that functions as a hub of the U.S. military and of defense contracting to institutions of higher education. The author is interested in the dilution of the word and legal definition. To write accurately about torture for this lexicon requires that the author ask the reader first to note how accustomed most readers in the United States have become to use of the word casually in polite company. The word “torture” has been used as a joke. As in, “this is torture!” People in the U.S. hear this word used in gridlocked traffic, while someone is trying on a swimsuit in front of a department store mirror, to describe a badly written song on the radio. The word “torture” has, through common parlance and also through film and television, become something rhetorically other than what it is, technically. Actual torture has also been diluted, visually, through the use of images on a screen.

Torture has been used repeatedly since September 11, 2001 in Western, popular culture, to entertain, to warn, and to frighten—from Game of Thrones to 24 to Homeland to complicated, story-driven video games. Actual people have been tortured as “human object lessons,” to use Marcus’s phrase, with originally limited, targeted viewing. And, at the same time, fictionalized depictions of torture have reached a wide, general audience. As recently as April, 2019, John Powers, a television critic for National Public Radio, summarized the popularity of Game of Thrones as “the world’s most popular show” at that time. Powers noted that “journalists are even writing elegiac articles about how, given our fragmented media environment, Game of Thrones may be the last TV series that everyone watches at the same time in order to be part of the conversation” (2019). While some journalists have been attempting for almost two decades to draw attention to a systemic, carefully orchestrated system of actual torture, watching (and commenting adroitly on) television series that depict torture has become a civic ritual, even a responsibility to be “part of the conversation.”

Seventeen years prior, in an essay for The Christian Science Monitor, Gregory M. Lamb noted the precipitous increase in television violence after September 11, 2001: “So much for media critics’ expectations that grisly fictional violence on TV would abate after the sobering events of September 11. Scenes of torture and sadism appeared on network entertainment TV at a rate nearly double that over the previous two years” (2002). Lamb also named in particular a Parents Television Council (PTC) study that reported, in 2008, the show 24 was depicting procedural torture as commonplace: “A Parents Television Council review found that 24 showed 67 scenes of torture in the first five seasons. [The main character of 24] Jack Bauer has been involved in more than 160 separate instances of violence since the show began (all six seasons) and has killed at least 71 individuals” (Lamb 2002). Other television programming was keeping up: “there were 110 scenes of torture on prime-time broadcast programming from 1995 to 2001. From 2002 to 2005, the number increased to 624 scenes of torture. Data from 2006 to 2007 showed that there were 212 scenes of torture” (Lamb 2002).

Bush and Cheney administration officials were open about their appreciation and emulation of the show 24. In a succinct, 2008 review of two (then recent) books on torture—Jane Mayer’s The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How the War on Terror Turned Into a War on American Ideals and Philippe Sands’s Torture Team: Rumsfeld’s Memo and the Betrayal of American Values—journalist Dahlia Lithwick begins by noting, “The lawyers designing [the Central Intelligence Agency’s] interrogation techniques cited Jack Bauer more frequently than the Constitution.” She continues, “according to British lawyer and writer [Philippe] Sands, Jack Bauer—played by Kiefer Sutherland—was an inspiration at early ‘brainstorming meetings’ of military officials at Guantanamo in September 2002.” Lithwick explains that “Diane Beaver, the staff judge advocate general who gave legal approval to 18 controversial interrogation techniques including waterboarding, sexual humiliation and terrorizing prisoners with dogs, told Sands that Bauer ‘gave people lots of ideas.’” Quoting Michael Chertoff, the Homeland Security chief, in his words to the Heritage Foundation about the show, it “reflects real life.” Lithwick continues: “Even Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, speaking in Canada last summer, shows a gift for this casual toggling between television and the Constitution. ‘Jack Bauer saved Los Angeles—He saved hundreds of thousands of lives,’ Scalia said. ‘Are you going to convict Jack Bauer?’” Lithwick concludes “The problem is not just that they all saw themselves in Jack Bauer. The problem was their failure to see what Bauer really represents within the legal universe of 24.”

Jane Mayer, the author of The Dark Side (one of the books reviewed by Lithwick) summarized the legal universe created by the show 24 in a 2007 essay for The New Yorker: “Each season of 24 . . . depicts a single, panic-laced day in which Jack Bauer . . . must unravel and undermine a conspiracy that imperils the nation.” She continues: “Terrorists are poised to set off nuclear bombs or bioweapons, or in some other way annihilate entire cities. The twisting story line forces Bauer and his colleagues to make a series of grim choices that pit liberty against security.” Mayer concludes that the show hinges on the choice, “invariably” for “coercion,” as, “[w]ith unnerving efficiency, suspects are beaten, suffocated, electrocuted, drugged, assaulted with knives, or more exotically abused.” And, “almost without fail, these suspects divulge critical secrets.

This “unnerving efficiency,” with which “suspects divulge critical secrets” is not only unnerving but in direct contradiction to the facts about gathering “intelligence” through torture. Lisa Hajjar draws on historical scholarship on torture in Europe to explain “its basic flaw was recognized since the Roman era: What it proves is the individual’s capacity to endure pain rather than the veracity of the statements elicited.” Hajjar quotes J.H. Langbein’s 1978 essay for the University of Chicago Law Review, “Torture and plea bargaining,” “Judicial torture survived the centuries not because its defects had been concealed, but in spite of their having been long revealed” (Hajjar 2009, 319). The visual loop of torture continues to be part of the concealing of both basic, logistical truth and a longstanding, principled, moral consensus unequivocally against torture.

In a 2005 New York Times essay “Normalizing Torture on ‘24,’ ” Adam Green notes a pattern that links different ways fear works politically-socially with how torture works politically-socially. Torture is, by one sociolegal universe, not only necessary to procure “intelligence” but creates ligaments to connect people in a social body. Suffering torture becomes a macabre form of bond. This is another way that torture has “worked” politically in the U.S. Green’s narrative summary is necessary to understand the perhaps counter-intuitive claim that torture has worked to domesticate torture.

“What is most striking about torture on 24 is how it affects not only politics but also emotional and professional relationships. The C.T.U. data technician Sarah Gavin, interrogated with tasers to discover if she were a terrorist mole, subsequently returns to work showing no signs of trauma. Indeed, she marshals the clarity of mind to renegotiate her terms of employment with her superior, who approved her interrogation just hours earlier. The war-protester son of Secretary of Defense Heller, more alienated than ever after a session of sensory deprivation in a C.T.U. holding room, receives a strikingly paternal lecture from his father about why that treatment was appropriate. Even Audrey’s husband, Paul, somehow rises above his grievance to view his erstwhile tormentor as a buddy, helping Jack extract documents from a defense contractor and fend off attack—and even loyally taking a bullet for him. In all of these interactions, torture doesn’t deaden the feelings between people, rather it deepens them. . . . It is often noted that torture goes against the tenets of human community in two fundamental ways. Because torturers deny the basic humanity of their victims, it’s a violation of the norms governing everyday society. At the same time, torture constitutes society’s ultimate perversion, shaking or breaking its victims’ faith in humanity by turning their bodies and their deepest commitments—political or spiritual belief, love of family—against them to produce pain and fear. In the counterterrorist world of 24, though, torture represents not the breakdown of a just society, but the turning point—at times even the starting point—for social relations. Through this artistic sleight of hand, the show makes torture appear normal.” (Green 2005)

Note that the creators of Game of Thrones elicited what Terri Gross called (approvingly) “a huge and fanatical international fan base” by way of repeated scenes of rape, graphic violence, and prolonged sequences of human beings torturing human beings. The title of that review was “Game Of Thrones Keeps Its Finger On The Pulse,” a phrase that warrants another question: What are the characteristics of a social body that has been trained to pulsate in this particular way (Powers 2019)?

The dilution of “torture” continues. “The Good Place” (2016–the present) is a television series produced in the United States specifically and explicitly about morality. The show has as its core conceit a universe in which the main characters are set up to be tortured for eternity by their proximity with one another. The show’s creator, Michael Schur, has explained his aim for The Good Place is to bring moral philosophy to a mainstream, television audience. Schur has literarily made torture a laughing matter. To quote the title of a Vanity Fair article: “The Good Place Makes Eternal, Hellish Torture So Hilarious.” Schur explains: “We’ve always tried to keep it sort of cartoon-y and silly, because what is actually happening is obviously awful for everyone.” He elaborates thus: “I have a 9-year-old son, and part of my thinking whenever we do something about how someone is being tortured is, ‘Would my 9-year-old son laugh at this?’ That’s the sort of target audience for that kind of joke is, a 9-year-old boy . . . I’ve gamed it out in my head” (Bradley 2017). One possible reading of the series is that it upends the logic of suffering in shows like 24 and Game of Thrones, depicting visually an alternative form of living together toward mutual flourishing. This fact of an era remains. During the same two decades when the United States might have been, under different circumstances, engaged in a United Nations investigation about U.S. sponsored torture, popular culture made “torture” a household word.

There are counterexamples. Yasiin Bey underwent the standard procedures for forcibly feeding a person imprisoned at Guantanamo Bay in 2013. Bey, known professionally in his career as a musician by the name Mos Def, underwent these procedures as part of a documentary directed by Asif Kapadia, in coordination with Reprieve, a human rights organization based in London, in an effort to bring awareness of the ongoing conditions at the U.S. military prison at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. In describing the effort, the Guardian notes, “in its fight against human rights abuses there is no substitute for the court of public opinion” (Ferguson 2013).

“Real patriots”

The actual facts of whether torture “works” to elicit intelligence have been established since the Greco-Roman era. Regardless of the court of public opinion, the courts of ethics have been clear about the morality of torture for decades. This is what must strike a reader at present. The United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment was established in 1984 and, from the outset, in Part I, Article 1 of its founding resolution, it defines torture as:

“. . . any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.”

There are multiple practices covered by this definition: prolonged and repeated pouring water into a human being’s face so that he or she feels as if they are drowning; forcing prolonged confinement in a small space alone, without even intermittent contact with another human being; putting another human being, while naked, into a freezing cold space, causing hypothermia; shocking another human being, while naked, on their genitalia; and forcing water into another human being’s anus. This is not an exhaustive list. These were some of the practices encouraged under the auspices of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency after September 11, 2001. These practices are not allowed under U.S. law and are explicitly disallowed under international law, including prohibitions established through the Geneva Conventions following World War II.

People working with and in the U.S. have been assigned the role of torturer; people have been assigned the role of assigning the role of torturer; people have assigned the roles of these practices, determining who is best suited to which role. And people have been assigned the role of popularizing the necessity of these practices. There have been organizations and working groups of psychologists, filmmakers, musicians, clergy and scholarly writers charged with the work of determining how to implement the “deterrent power” of torture in the United States and abroad (to use Joel Marcus’s phrase again). To paraphrase General Dwight D. Eisenhower in his departing speech, torturing other human beings became, after September 11, 2001, an industrial complex. Again, when threatened with psychologically acute pain, most human beings will respond with an answer that the executioner of such pain seems to be eliciting. But torture may “work” in that it may spread fear across a region, a nation-state, a village, or a family.

Scott Horton is an investigative journalist who has written extensively on U.S. sponsored torture. In his 2015 essay for Harper’s Magazine, “Company Men: Torture, treachery, and the CIA,” Horton writes that when “the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence released its torture report—or, more accurately, a redaction-studded version of the report’s executive summary . . .

the authors avoided the tepid style of most congressional prose, opting instead for a clinical, precise, and engaging narrative that patiently unfolds one of the most dysfunctional and embarrassing episodes in the history of American spycraft.” Horton contrasts the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s narration with a story that was much more popularly regarded as truthful, a 2012 movie directed by Kathryn Bigelow, starring Jessica Chastain as a CIA operative serving on a team to use supposed intelligence to carry out the execution of Osama bin Laden. The Senate report “makes for an instructive comparison with Zero Dark Thirty, which was written and produced with the CIA’s secret backing. The film tells the story of post-9/11 intelligence in the way Langley [a metonym for the Central Intelligence Agency] would like to have it told. But the Senate report unmasks the film as sheer fiction.” The report “has the distinct advantage of being true.”

This course of events was not inevitable. It was possible that the United States could have embarked on a thorough, public reckoning with the facts eventually highlighted by the (partial) publication of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s report in 2014. But, there were new “objects of apprehension and concern” (to use Robin’s phrase) in the form of “ISIS” (the Islamic State) and November elections for members of the U.S. Congress. During an August, 2014 press briefing, Barack Obama, then in the middle of his second term as President of the United States, responded to a question about the Senate report by referring to people involved in the practice of torture as “real patriots,” conceding that, although “we tortured some folks,” and that torture is “contrary to our values,” the acceptance of torture as a necessity is ethically conceivable. To quote from that briefing, President Obama explained, “I understand why it happened. I think it’s important when we look back to recall how afraid people were after the Twin Towers fell and the Pentagon had been hit and the plane in Pennsylvania had fallen, and people did not know whether more attacks were imminent, and there was enormous pressure on our law enforcement and our national security teams to try to deal with this.” He continued, “it’s important for us not to feel too sanctimonious in retrospect about the tough job that those folks had. And a lot of those folks were working hard under enormous pressure and are real patriots” (Kludt 2014). His wording encourages empathy not only for the enlisted men and women expected to carry out torture, but for the people above them in the hierarchy who created the moral and legal architecture that made torture seem plausible.

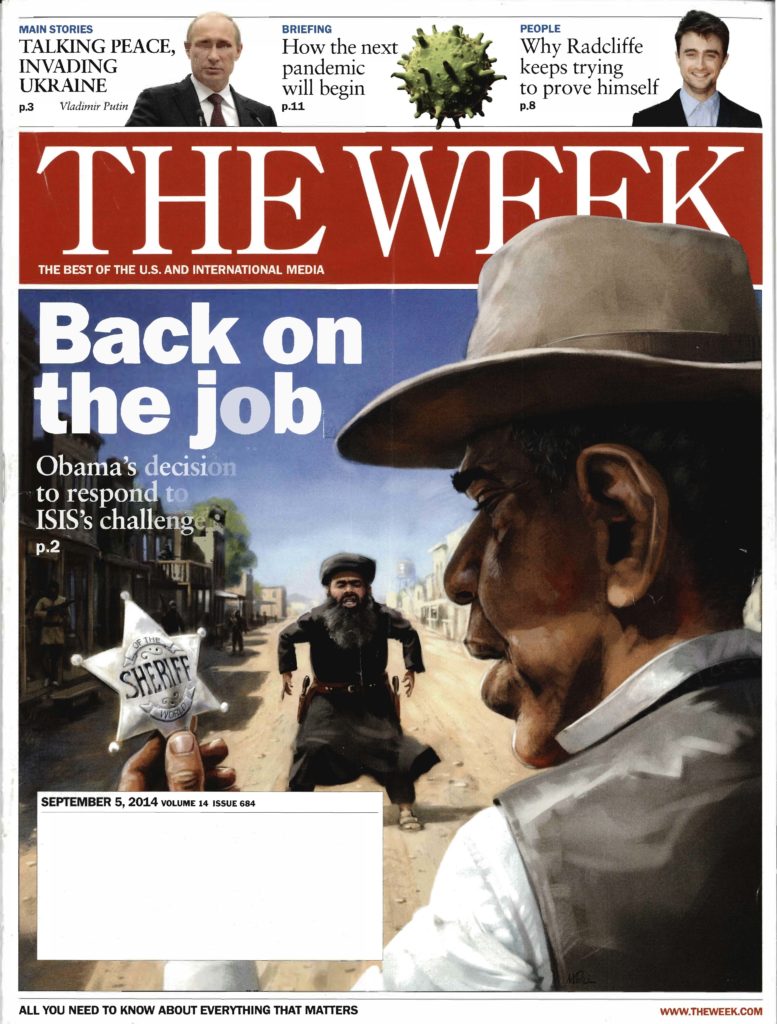

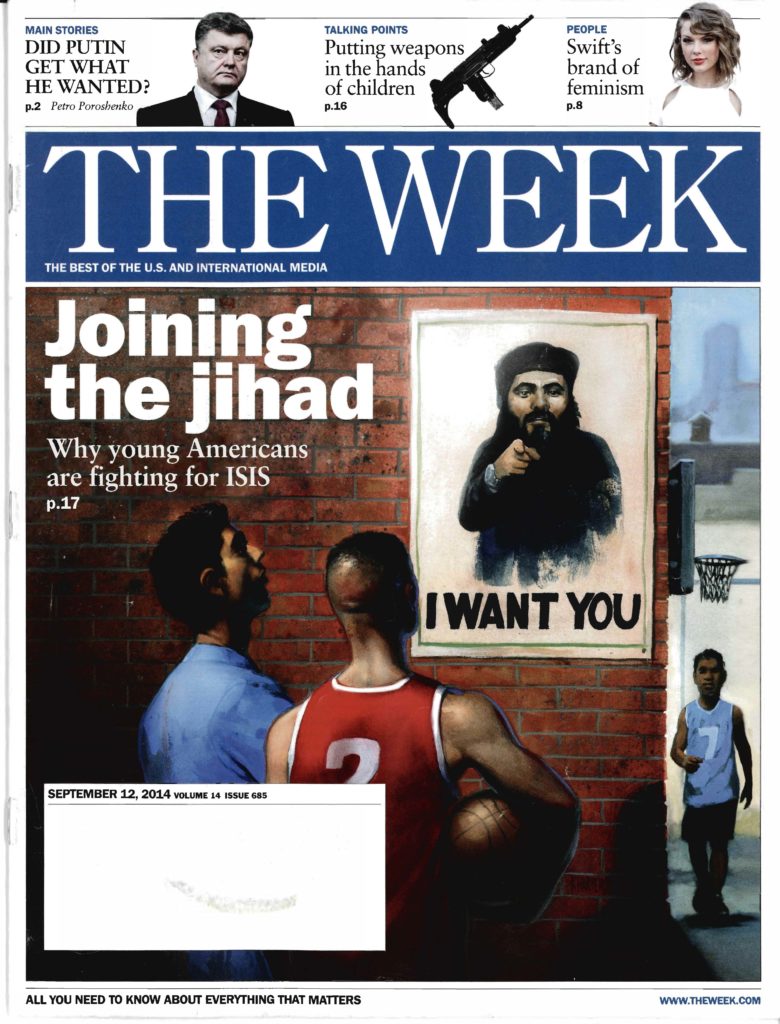

In order better to understand the court of public opinion created at that time, and thus President Obama’s own political options, it is helpful to note two images from a media source distributed widely in the U.S. in 2014. The line running underneath the address label for The Week was, in 2014, “ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT EVERYTHING THAT MATTERS” (Capitalization in the original, 2014). In September of 2014, the two editions serving as parentheses around September 11, 2014 featured images about “ISIS.” In the September 5, 2014 edition, the highlighted article was “Back on the Job: Obama’s decision to respond to ISIS’s challenge,” with a political cartoon on the cover featuring Barack Obama, looking directly at a badge that would be known to most readers in the U.S. as a sheriff’s badge from the “Western” classic High Noon. That storyline asks a basic question about a man’s willingness to engage in a showdown against a murdering gang. In this case, the object of “apprehension and concern” is personified by a caricature of another man with brown skin, with a beard and a turban. The badge is engraved with the word “SHERIFF” and “OF THE WORLD.” The Week also announced “The Best of the U.S. and International Media” on September 12, 2014, with a related image, of two young men looking at the image of a poster featuring a Muslim imam pointing, in a style referencing the Uncle Sam military recruitment poster from the U.S. in World War I and II, with the words “I WANT YOU” across the bottom. Two young men with brown skin are looking up at the poster. One young man has on an athletic jersey and is holding a basketball. To the side of the drawing is another brown-skinned young man with an athletic jersey, walking away from a basketball court and toward the poster. The racial dynamics are not subtle. Would the first African-American President of the United States be up to the task of performing as Sheriff of the World, or, as the second image implies, would he be on the side of the three other brown-skinned young men, “Joining the jihad.” (xxii)

Postscript

Joel Marcus writes in his essay on crucifixion: “The greater the insolence, the higher the cross; the proper response to excessive haughtiness was, in the words of the Clint Eastwood film, to ‘Hang ‘Em High!’” If the work of torture in the years after September 11, 2001 was in part to strike fear and deter haughtiness, and if the work of torture on television was in part to dull the sense that torture is neither moral nor normal, then it is my hope, as a citizen and a scholar in religious ethics that people will summon defiance and clarity. At a 2011 conference held in Durham, North Carolina, “Toward a Moral Consensus Against Torture,” Scott Horton named as a possible, very unintended consequence of the U.S. program in torture the acceleration of resistance that came to be known as the “Arab Spring.” With the 2004 publication of images of U.S. coordinated torture of human beings at the Abu Ghraib prison, Horton proposed, people suffering under dictatorships in the region gathered courage to resist regimes held up through a combination of foreign (often U.S.) aid and torture. This possibility, that, contrary to American grand strategy, the exposure of actual torture may have elicited such courage helps this author to continue her pursuit of our common discipline.

References

Bradley, Laura. 2017. “How The Good Place Makes Eternal, Hellish Torture So Hilarious.” Vanity Fair. Accessed September 11, 2019. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/09/the-good-place-season-2-premiere-mike-schur-interview.

Ferguson, Ben. 2013. “When Yasiin Bey was force-fed Guantánamo Bay-style – eyewitness account.” The Guardian. Accessed September 11, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/world/shortcuts/2013/jul/09/yasiin-bey-force-fed-guantanomo-bay-mos-def.

Green, Adam. 2005. “Normalizing Torture on ‘24.’” The New York Times. Accessed September 11, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/22/arts/television/normalizing-torture-on-24.html.

Hajjar, Lisa. 2009. “Does Torture Work? A Sociolegal Assessment of the Practice in Historical and Global Perspective.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 5: 311‒345. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.093008.131501.

Horton, Scott. 2015. “COMPANY MEN: Torture, Treachery, and the CIA.” Harper’s Magazine, 04: 84-88.

Kludt, Tom. 2014. “Obama: ‘We Tortured Some Folks.’” Talking Points Memo. Accessed September 11, 2019. https://talkingpointsmemo.com/livewire/obama-we-tortured-some-folks.

Lamb, Gregory. 2002. “TV’s Higher Threshold of Pain.” The Christian Science Monitor. Accessed September 11, 2019. https://www.csmonitor.com/2002/0823/p13s02-altv.html.

Lithwick, Dahlia. 2008. “Lithwick: How Jack Bauer Shaped U.S. Torture Policy.” Newsweek. Accessed September 11, 2019. https://www.newsweek.com/lithwick-how-jack-bauer-shaped-ustorture-policy-93159.

Marcus, Joel. 2006. “Crucifixion as Parodic Exaltation.” Journal of Biblical Literature, 125: 73–87. https://epdf.pub/journal-of-biblical-literature-vol-125-no-1-spring-2006.html.

Mayer, John. 2007. “Whatever It Takes: the politics of the man behind ‘24.’” The New Yorker. Accessed September 11, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/02/19/whatever-it-takes.

Parents Television Council. 2008. “Parents Beware of 24.” PTC’s Weekly Wrap. Accessed September 11, 2019. http://www.parentstv.org/PTC/publications/emailalerts/2008/wrapup_112108.htm.

Read, Catherine. 2018. “Torture Flights: North Carolina’s Role in the CIA Rendition and Torture Program.” Accessed September 11, 2019. https://www.nctorturereport.org/pdfs/NC_Torture_Report.pdf.

Robin, Corey. 2004. Fear: The History of a Political Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. 2014. “Report of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Committee Study of the Central Intelligence Agency’s Detention and Interrogation Program.” 2014. Accessed September 11, 2019. https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/sites/default/files/publications/CRPT-113srpt288.pdf.

United Nations Human Rights. 1984. “Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.” Accessed September 11, 2019. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CAT.aspx.

Linen Theme by The Theme Foundry

Copyright © 2025 Amy Laura Hall. All rights reserved.