Brokeback Mountain and Moonlight, with Love

This essay was published in the Durham Herald-Sun on Sunday, December 4, 2016.

This essay was published in the Durham Herald-Sun on Sunday, December 4, 2016.

When my older daughter was at Riverside High, the theater program performed “The Laramie Project,” a collaboration of author Moises Kaufman, people in Laramie, Wyoming, and members of the Tectonic Theater Project. It was performed first in 2000 and uses multiple voices to tell a real story, the 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard. The event that precipitates the production, every time, is the brutal death of a young man murdered because he is gay. The story begins with a tragedy.

Annie Proulx set her 1997 short story “Brokeback Mountain” in Wyoming. She opens with these words:

They were raised on small, poor ranches in opposite corners of the state, Jack Twist in Lightning Flat, up on the Montana border, Ennis del Mar from around Sage, near the Utah line, both high-school drop-out country boys with no prospects, brought up to hard work and privation, both rough-mannered, rough-spoken, inured to the stoic life.

This love story ends as Jack is murdered with a tire-iron after attempting, finally, to stop living a lie. Ennis offers to help Jack’s parents take his ashes to Brokeback Mountain. Jack’s mother, who Proulx implies has a clue and a heart, offers for Ennis to visit Jack’s boyhood bedroom. Proulx describes what Ennis finds:

The shirt seemed heavy until he saw there was another shirt inside it, the sleeves carefully worked down inside Jack’s sleeves. It was his own plaid shirt, lost, he’d thought, long ago in some damn laundry, his dirty shirt, the pocket ripped, buttons missing, stolen by Jack and hidden here inside Jack’s own shirt, the pair like two skins, one inside the other, two in one.

Proulx’s prose and characters are so familiar I can visualize their gait, hear the cadence of their voices. I grew up loving men who are “inured to the stoic life.” Texan Larry McMurtry co-wrote the screenplay with Diana Lynn Ossana for the 2005 film. I have not seen the movie. I knew too many boys and girls suffocated by a setting where they could not live the truth of daylight. The only suicides I knew growing up were of people who others whispered about, often with a tsk tsking that implied death was better than living gay. As one friend wrote, a town like my hometown is a place “you dearly love but never feel relaxed in.”

People have, in my hearing, used the words “Brokeback Mountain” as a derision, drawn from a visceral fear of men who are gay in secret. This is absurd, given these same people do not want anyone to be gay not in secret. Fear of the undetected gay coupling is a nonsense that acknowledges God makes some of God’s beloved children gay, linked to a refusal to bless love between two gay people. This nonsense is written into movies attended by congregations as a fellowship outing – where men marked as “effeminate” are mocked, used as comic relief in supposed morality plays or to accelerate comedy in self-loathing slapsticks about “family life.”

[Let those with ears to hear, please hear. You know what I am talking about.]

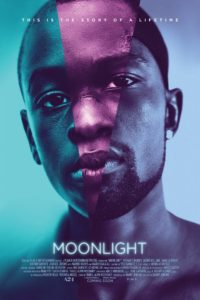

I am grateful for the 2016 film Moonlight. I am grateful the Carolina Theatre brought this to Durham. The film is based on a play by Tarrell Alvin McCraney, and the screenplay was written and directed by Barry Jenkins. McCraney and Jenkins offer a blessing that does not mock or evade hatred. McCraney and Jenkins have also offered a story that shows a man coming out in a way not linked to death. They wrote neither a comedy nor a tragedy. They wrote a life.

In his November 4, 2016 essay “The Sad, Surreal Experience of Seeing an Audience Laugh at Moonlight,” E. Alex Jung writes:

It was a Friday night . . . and the screening was completely sold out. Early on, though, one scene made me realize I might have picked a bad audience: It’s in the first third of the movie, where our young hero Chiron is sitting at the dining table with his surrogate parents, Juan and Teresa (Mahershala Ali and Janelle Monáe). He asks them, point-blank, “What’s a faggot?” It’s a moment that feels like a gut punch. When I first saw it, I held my breath, waiting to hear what Juan would say. He explained that it was a negative word used to describe men who liked other men. Then came the next question, “Am I a faggot?” A group of women behind me started giggling at the first question and were full-on laughing by the second — so much so that they drowned out Juan’s response. I was perplexed: Were we watching the same movie?

I pray people will see the film. I pray people will hear and, eventually, not laugh. And I fervently pray that children from Texas to Wyoming to Durham, North Carolina will see on screen the possibility of their own beautiful truth.