Fight for your Right to Daaaaadddyyy! The Art of Fatherhood, MCA, and Wild Things

This Father’s Day, we celebrate my Dad’s retirement from 47 years of ministry in the United Methodist Church. He has been the spiritual abba for three generations of children, from Sparrowbush, New York to Rhome, Texas. A few days ago, a room full of Methodist clergy in the Southwest Texas voted to allow him to retire. (Methodists vote on everything.)

At the same meeting, we held a group of brand new clergy to a set of rules that are just plain odd. (The questions Methodist pastors have to answer about “being made perfect” are strange enough for a post all their own.) For this post, I want to note that the Methodist rules contain at least two promises not to “trifle,” and several promises to perform “diligence.” My bishop’s favorite rule is “Will you diligently instruct the children in every place?” He asks this of the candidates each year with notable verve. John Wesley was all about diligence, and he had no patience for anything that whiffed of trifle. I think he was off the mark, because good fathers, and good pastors, have to learn to waste serious time if they are going to instruct children.

Parenting as Sand Mandala

One of the ways I survive the interminable meetings that make up Annual Conference each year is to walk the Corpus Christi coastline. I was mentally sorting through this blog post when I read a sign: Earth without Art is just “Eh.” Clevah. While watching the jumping fish (yes, really) I thought also about something that Felix Salmon said on a Slate podcast regarding money and art: “Expensive art tends to be quite big . . . Expensive art often tends to be red . . . Remember we are talking about multi-millionaire men here with big egos . . . and there are certain types of art that multi-millionaire men with big egos like . . . art with naked women in it tends to go for more money.” Big, red, naked-woman art costs more, because men with ego issues like big, red, naked women . . . I doubt that expensive art does much to make the earth less “eh.”

But, regarding men, and egos, and art, men who are responsible for children have to learn the art of trifling – the art of doing things that might feel totally unproductive and even be totally unproductive, because children require a kind of attention that is more like working on a small sand mandala than on an expensive, red, naked-woman painting. Life with children requires fighting for our right to little tea parties, and learning to boogie to Abba’s “Dancing Queen” like no one is watching.

Forgive me, but I simply must now tell a story in which I am the hero. (This is an obnoxious kind of story to tell, but, it is too on-point to leave out.) Rachel was about 3, and she and I were boarding the plane to go to the AAR together, when another, senior scholar looked at Rachel, smiled, and wondered a bit at the fact that I was bringing her with me. “You know,” he said, “I have never been able to communicate with children.” Huh, I thought, that is strange. The man had two grown children, and a school-age daughter from his recent, second marriage. It hit me that, either he was being too modest, or else he had never needed to get one of his children to eat, or to dress, or to sleep. To get through a normal day as a dad, you have to learn somehow to be silly – to learn artistically to trifle and to set far aside what usually counts as diligence.

Beastie Boys and Girls

My college boyfriend loved the Beastie Boys, so I tried to like them, and, with practice, I came to enjoy them. The guys at the local bike shop were impressed when 4 year old Emily could identify one of their more raucous songs on the radio. It was a proud moment. I was not sure how to feel when I found out, during commentary about Adam Yuach, that they had apologized for some of their sexist lyrics. I am also not sure how to feel about the fact that I did not immediately know how to feel. But I do know that their music makes me set aside all pretense of being serious, or morally righteous. I just want to dance. When I put on their music in the car, my girls have to remind me that, in the words of Wanda Sykes, “white people are looking at you.”

My college boyfriend loved the Beastie Boys, so I tried to like them, and, with practice, I came to enjoy them. The guys at the local bike shop were impressed when 4 year old Emily could identify one of their more raucous songs on the radio. It was a proud moment. I was not sure how to feel when I found out, during commentary about Adam Yuach, that they had apologized for some of their sexist lyrics. I am also not sure how to feel about the fact that I did not immediately know how to feel. But I do know that their music makes me set aside all pretense of being serious, or morally righteous. I just want to dance. When I put on their music in the car, my girls have to remind me that, in the words of Wanda Sykes, “white people are looking at you.”

I meant to write a shout-out to Yuach right after his passing, but I was busy boogying and doing dishes. So consider this my holler of thanks, as a teacher as well as a mom, because their “Fight for your Right” has long been a mainstay of my lecture on masculinity and work. This may seem a strange theme song for me to encourage in my male students. (Yes, the lyrics mention smoking and porn.) But, for a while now, one goal in my teaching about manhood has been to encourage more teenage boys to recognize what one kid did at the Duke Youth Academy years ago. (I am not the hero of this story.) I was lecturing on embodiment and baptism and getting off the rat-track of success, and we got to the point about teenage pregnancy. I gave my usual spiel against shame, and a young woman rightly balked; boys who become fathers can remain safely hidden. At this point, one young man said, with all earnestness, “But, if what she said about baptism is true, then I am already a dad. The kids in the church are already mine.” Wow.

The Mothers’ Day cover of the New Yorker caught me off guard this year. I couldn’t figure out the joke at first, because it wasn’t marked as a holiday issue. The image of all those men (even male birds, ha!) hanging out with kids didn’t strike me as noteworthy. Truth be told, I thought the one woman in the mix must be thinking it was her randomly lucky day at the park! But, as Michael Chabon writes in his commentary on fatherhood, men who take time to trifle with kiddos are still a rarity. Being a “father” of the faith still sounds more like a call to speak from a pulpit, or to serve on the church finance committee, than a summons to sit on your ass in a sandbox. That youngster at the Duke Youth Academy got it, a sneak preview of life for men who daily live with children. To paraphrase one of my favorite scenes ever (love John Cusack), much of fatherhood isn’t about selling anything, buying anything, or processing anything. It isn’t about selling anything bought or processed, or buying anything sold or processed, or processing anything sold, bought, or processed, or repairing anything sold, bought, or processed . . . Lloyd Dobler just might make a great dad.

The messaging about real manhood toggles wildly today between the work-your-butt-off model and the have-a-huge-barf-your-head-off-party model. The partying for which men are apparently to fight has lots to do with hiring hookers and hurling and less to do with singing “Rocky Top, Tennessee” for the infiniteenth time with a second-grader. Adam Yuach put this well in an interview about his own worldly success and search for faith: “In a sense, what Western society teaches us is that if you get enough money, power and beautiful people to have sex with, that’s going to bring you happiness. That’s what every commercial, every magazine, music, movie teaches us. That’s a fallacy.” Yep. The big dudes who dictate the supposed value of art may want giant, blood red titties on their wall, but true beauty is smaller, and, as I submitted a long time ago in this article, more fun.

Learning to Care

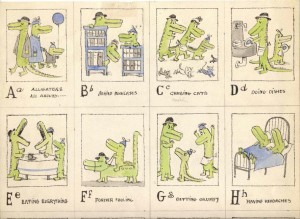

I love Maurice Sendak. I love his drawings of fussy old hen in A Kiss for Little Bear (an all time favorite) and I love love love the way the grown-up alligators are “forever fooling” on each page of Alligators All Around. And, of course, I love Where the Wild Things Are, in which the monsters are modeled after Sendak’s overwhelming extended family.

In this interview with Bill Moyers, I found a dozen new reasons to love Sendak, including this fabulous quote about Emily Dickinson: “She is so brave; she is so strong; she is such a sexy, passionate little woman.” Art was a kind of “salvation” for Sendak, and he often read Emily’s poems to inspire him when courage faltered. His fragile but tenacious courage allowed him not only to fly up into the stratosphere of the night kitchen, but also to dig into the dirt of, well . . . dirt. According to Sendak, books for children must deal with mortality, with the dust to dust terrors of life, because children are already very aware that their little existence is both delightful and dangerously expendable. Maurice Sendak was not a “father” per se. Perhaps he never had to coax a kid to drink her milk or brush her teeth, but he sure did learn how to communicate with children.

In this interview with Bill Moyers, I found a dozen new reasons to love Sendak, including this fabulous quote about Emily Dickinson: “She is so brave; she is so strong; she is such a sexy, passionate little woman.” Art was a kind of “salvation” for Sendak, and he often read Emily’s poems to inspire him when courage faltered. His fragile but tenacious courage allowed him not only to fly up into the stratosphere of the night kitchen, but also to dig into the dirt of, well . . . dirt. According to Sendak, books for children must deal with mortality, with the dust to dust terrors of life, because children are already very aware that their little existence is both delightful and dangerously expendable. Maurice Sendak was not a “father” per se. Perhaps he never had to coax a kid to drink her milk or brush her teeth, but he sure did learn how to communicate with children.

My own dad did not read Sendak books to me. He made up “Mortimer stories” – stories about a boy named Mortimer and, when I protested, about his sister Mortimeria. And, along the way, he also told me stories about whose I was. I learned that faith is not something solid, not a block of clear TRUTH that I was given to then carry about with me like a weapon or fix-it-all salve. Faith is something more elusive, and even whimsical, more received unaware than grasped. And, here, I can’t help but tie in Sendak’s Pierre, wherein a little boy learns to care after he is eaten by a lion. The story revolves around a defiantly apathetic boy named Pierre. He DOES NOT CARE. That is the refrain. His parents coax, but he is immovably taciturn. Then, left alone, he does-not-care himself right into a lion’s belly. Presumably due to Pierre’s sourness, the lion gets a tummy ache and, after a bit more silliness, Pierre emerges and, HE CARES! The story is ridiculousness with a singsong rhyme; Pierre is about as nonsensically cruel as original sin and as beautifully foolish as salvation.

This entry ought to end with a story about my dad as a hero, don’t you think? When he taught my confirmation class, I asked interminable questions and, at the end of the course, I was still uncertain. I just wasn’t sure I believed all that we were supposed to stand up and say we now believed. He told me I didn’t have to be confirmed yet. He told me that he also still struggled to understand what he believed. And he asked me to consider that maybe standing up in confirmation meant promising, for the rest of my life, to keep trying to know God through Christian faith, and to know that I am known by God.

This Fathers’ Day, I am more certain than ever that life is as nonsensical as not-caring for no good reason and as miraculous as receiving the capacity to love after being barfed up by a hungry lion with big teeth. But I also, most days, know whose I am. And for that, I have a different parent to thank, the only parent who is perfect, if also utterly baffling. I would encourage all the fathers out there reading to lean on that Father, and to risk the public spectacle of trifling each day. Pray for it when you pray for your daily bread.

PS:

More on Maurice Sendak and the terrors of childhood:

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/culture/2012/05/art-spiegelman-discusses-maurice-sendak.html

And, just because I love her, Carole King singing Pierre and Alligators All Around (the illustrations for the latter sadly lack the grown up alligators, but the tune is fun).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=70U47cNi7sA&feature=fvwp&NR=1

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r3DRUJUWgOA

Finally, this is the Slate Culture Gabfest re Maurice Sendak and also Art Market Economics: